Composing products with capabilities, features, and outcomes

Product Compositional Atoms

When we think about products, we often think about capabilities and features. We think about a product's technologies and functionality that a customer want to pay for. I think this is "inside out" thinking. I want to show you how to think about user outcomes first and how to compose them from smaller atomic ideas.

Thinking inside out

Let's think about some of the common concepts you might encounter working in product as a product manager, designer, or developer. We have:

- capabilities: technologies, algorithms, automation, machine learning models, and other "cool tech" in your portfolio of assets

- features: tools and abilities you give your users to do something

For sake of discussion, let's call these things "product atoms": small indivisible pieces that can compose together to create product experiences. This idea of composition is important, so remember it for later.

These are where we tend to spend much of our time thinking about our products as we're designing or imagining things we can develop to bring to market, with the ultimate goal of differentiating from competitors and winning a segment.

But here's the thing: these terms describe your company; they do not describe your customer's journey. Thinking this way limits us to "inside out thinking" where we can only serve customers who fit our molds. You are limited to seeing the world within the boundaries of the paradigm that define your existing product or prototype. And because of that, you won't see new customer segments you could serve or how you could serve existing customers in new ways.

Worse, we find ourselves with the classic problem of inventing hammers looking for nails to hit -- a capability or feature unmapped to a customer problem is a potentially expensive burden in search of product market fit.

How did we get here?

I don't want this to be condemning; I only know this idea well because it has happened to me so often in my career. When I spent most of my time as a software developer, I often worked on side projects. I would be really excited about them over the weekend but then watched them wither and died by the end of the following work week. Without good timing and a compelling pitch, disruptive technology often fails to "cross the chasm" and disrupt the company roadmap.

This happens to developers who are more engaged with cool technology than they are with customer outcomes. But we shouldn't fault them! This is an important part of the product life cycle and we need a fresh and vibrant portfolio of capabilities to fuel our vision of what's possible.

This happens to product managers, too -- especially as we're growing in experience and seniority. The temptation to launch the next killer feature and get your name on the "ship it" announcement is strong. And it should be; the hunger to ship things is important to the culture at any organization.

But without paying attention, our feature or our swim lane becomes the only thing we can see. To make our assigned area as successful as possible, we look for ways to magnify it and try to consume the entire product with our area of ownership. Everybody wants to have that killer feature that makes your product sing, but a single feature doesn't make an entire product experience. It loses sight of the holistic customer experience and puts the burden on them to think about how to use that feature to solve a problem.

So why should we focus on maturing from this seemingly productive place? Because it's still about the company, not the customer.

Thinking Outside In

Instead we can think of customer outcomes. A customer doesn't want to buy access to "feature XYZ". They want to solve a problem. They want time back in their day.

They want to be the hero of their story where your product naturally comes alongside and guides them to success.

To get to this mode of thinking, we shift our perspective to think of the user first. We think about their motivations, their contexts, and their resources -- or lack thereof. We think about what problems they want to solve and what help they need to solve it. We organize patterns of customer similarities into concepts commonly called "personas".

More importantly, we need to understand what paths and journeys they may take to solve that problem: it may not be the same for all users and it may not be obvious in your tool's architecture today. We commonly know these customer pathways as "workflows". Ideally, your product's UX and navigation map to those workflows, but they don't always! You might work on a product whose information architecture has drifted from common workflows.

More likely is that multiple workflows will share features and capabilities. It's natural for them to overlap and still result in different outcomes.

Mapping outcomes to features and capabilities

Remember the idea of composition?

A workflow is an outcome a customer achieves in your product by leveraging features and capabilities in your application.

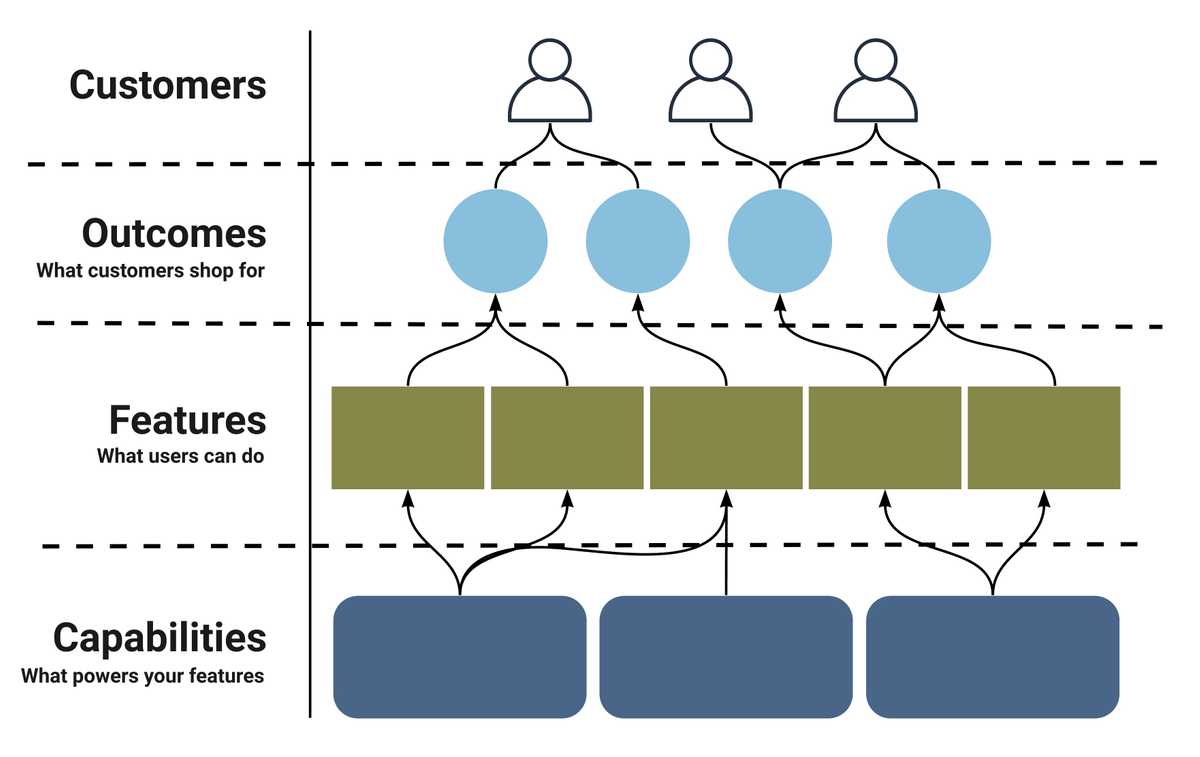

In this example diagram, we start with customers who want to achieve a specific outcome. These customers may have different needs and you see have outcomes in common and some are completely different that only want one thing from your product. Each outcome is composed of one or more features and a feature can be part of more than one workflow. Those features are powered by capabilities.

When you encounter new customer workflows and outcomes, you can think about what things they need to do to solve those problems. These tools, helpers, and data map to your features. Then you can understand what features already exist and which ones you need to create. Then you can look at what capabilities power those features or understand what capabilities you need to invest in to unlock those features.

More importantly, this lets you think across your product to shift your perspective to how your customer views it from the outside.

Addressing emerging technology

Even though I've painted this spectrum of outside vs. inside thinking, I can't advocate for abandoning one over the other. Developers are still going to explore and we're still going to encounter emerging technology that we want to understand how to leverage.

This is the innovative part of product management I really enjoy. To do this well, you need to be able to bounce quickly between internal perspectives and external perspectives.

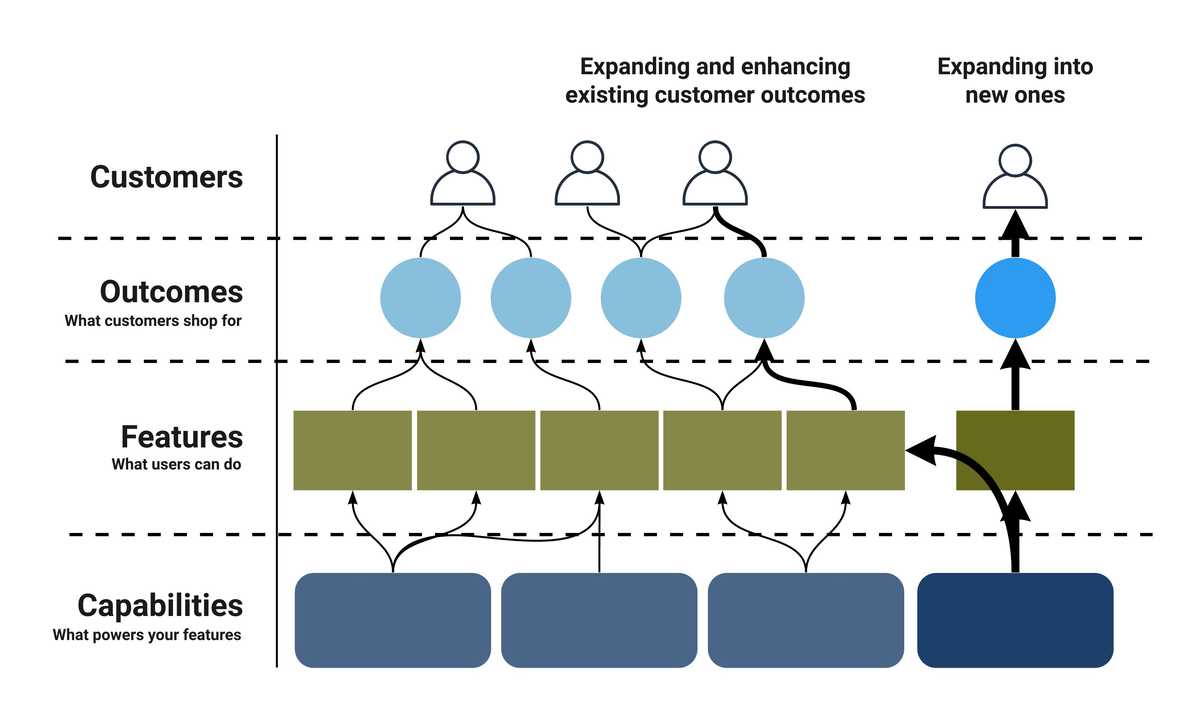

You need to be able to evaluate new technologies and think "what existing workflows are extended or improved by this technology"? The temptation is to ask "how can I take this capability straight to a customer and sell it to them" without first asking what problems they solve. Again, you would be putting the burden on the customer to figure out why they want it and how to use it.

It also lets you think about "what new questions does this let me ask?"

You need to be able to predict what kinds of problems a new capability might address and then talk to people who think about those problems. They might not be customers in your current addressable market today. And if not, that's exciting because it might mean you are uncovering an opportunity for the organization to expand its addressable market segments and capture new value.

But you still need to prove there are real customers who will pay for real outcomes. You need to ask good questions and uncover workflows your product could support. Then you need to map back to features and capabilities you could compose to produce that workflow and estimate your ability to produce them.

And if you've done all that, you can neatly map together how your product atoms compose to produce a solution. You'll be able to speak to how a new capability can unlock multiple outcomes across your product. You'll become a better partner to your other product managers because you're thinking about how a customer's journey flows in and out of everyone's area of ownership.

Wrapping up

Learning to think outside in means getting really good at finding interesting questions to explore. But it also means getting really good at knowing your portfolio of product atoms and composing them in your head to pattern match them to customer workflows.

You want to spend time with your data scientists, software engineers, and designers to know what's possible. You want to spend time thinking about your features and how they fit into the customer's bigger story.

But you never want to misidentify a new capability or feature as the entire world in your point of view. Your customers don't see it that way and neither should you or your product design.

Have fun exploring! Find cool stuff. Get to know your customers and help them achieve their outcomes. Build amazing things.

Do you have any questions or ideas you'd like to share? Let's discuss on Twitter or on LinkedIn.