Local Domain NAP Audits

I want to share some tools and tricks with you. More specifically, I want to explain a process I follow that is an interesting and unique puzzle each time I do it. I'm going to talk about finding web pages for all store locations in a company's domain and extracting information from them.

"Interesting and unique" can describe something fun, and this exercise usually is fun for me. I encounter or learn something new each time.

It's not that fun when you're pressed for time, though. Creating a scraping solution from scratch each time can feel like an exercise in futility. I want to try to demystify what's happening and offer some things I use to make them faster.

Terms and Definitions

Let's cover some terms first. If you're already familiar with local SEO, these are probably familiar to you already and you may want to skip this section:

- NAP

-

Stands for "Name, Address, Phone Number". The components that make up the identifying information for a store or business location. Sometimes accompanied by Website and Categories. Think of it as the digital fingerprint for a business.

- Citation

-

I like to think of this as a "mention" of a business anywhere on the web, usually by its NAP.

I like David Mihm's definition. It may be a bit old by now, it is how I formed my understanding:

...the difference is that these “links” aren’t always links; sometimes they’re just an address and phone number associated with a particular business! In the Local algorithm, these references aren’t necessarily a “vote” for a particular business, but they serve to validate that business exists at a particular location, and in that sense, they make a business more relevant for a particular search.

- Domain

-

The web address for a set of related pages. In this URL,

www.thedahv.comis the domain—specifically a sub-domain of thethedahv.comdomain. For this discussion, we'll simplify and refer to everything as a domain, but know thatwww.thedahv.comandsomething.thedahv.comare considered different.In this context, it means the domain and the set of pages owned and managed by a business with many store locations. We'll be focusing on these pages.

- Store Locators and Landing Pages

-

A web page with an index or search function of all stores managed by a company. For example, I can punch my zip code into a page on Fred Meyer's store locator page to find a store near me.

Meanwhile the page for a specific store location is sometimes called a "landing page" in the context of local SEO. For example, here is the page for the Ballard store where my family normally gets its groceries.

- Aggregators and Directories

-

Data companies and web sites that collect and publish data about businesses within a market. Some focus on specific industries or emphasize a specific user-experience. Some are more important than others, but the takeaway is they represent citations for businesses on domains not owned or managed by those businesses.

These are important, but they are not a focus of this article.

- Consistency

-

If you ask a bunch of local SEOs and marketers, ensuring all citations for your business are correct, complete, and consistent across the web is important. In fact, it is foundational to successfully leveraging search engines as a marketing channel.

That was a lot of information, but you should be equipped to understand the rest of the non-technical material if you made it through.

Defining Domain NAP Audits

As mentioned, managing NAP consistency across web citations is important to digital marketing of local businesses. We're going to refer to a "domain NAP audit" as the act of ensuring correct NAP data on store landing pages on a company's domain.

The overall process is:

- Find the URLs for all stores in a domain

- Find where the store NAP data is contained within the page HTML structure

- Fetch and extract the NAP data

- Export it to a file for analysis and sharing

So who is the audience for this post?

- In-house marketing or store management teams. I hear centralized locations data management is actually pretty hard for organizations to do. Getting this data together quickly and repeatably should be easier to do.

- Marketing agencies. Finding a client or prospect's stores and analyzing the results gives you an advantage if you can do it quickly, independently, and repeatably.

- Software engineers. If you work at a startup, or are on a product team with marketing support, there is a lot of room for you to lend your technical perspective to these problems, ensure SEO best practices from the codebase, and help your marketing team move faster with cheaper tools.

I am in the last group. I worked at a startup that had no product marketing or dedicated SEO support, so it fell on programmers to learn about making our work and content easier to discover.

On the other end of the spectrum are organizations with marketing teams working independently of the technology teams. My bet is with more planning and collaboration with technology groups earlier in a project, marketing teams can do this kind of work much more quickly.

Some Assumptions

Before we begin, we have to make sure some assumptions hold true for each situation:

- The domain hosts a machine-readable index of URLs for all its stores, or a store-locator page we can scrape for these URLs

- The pages are structured in a consistent way—i.e., the NAP is in the same place on every landing page

- The pages are rendered statically—i.e., NAP data isn't rendered by JavaScript after the page loads

- The NAP data is tagged or marked up in a structured way such that a program can extract it from HTML

This won't be true of every domain you research. You may have to adapt, find workarounds, and reach for different tools. However, if the company you're researching fits these criteria, you should be able to use these strategies.

Technical Nerd Content Advisory

WARNING: this is going to be a pretty technical post. There will be shell script snippets below, and I'll do my best to annotate what is happening in-line.

Regardless of your role or experience, I think you can learn this stuff.

These are the command-line tools I'll be using in the examples. I encourage you to check out each one, understand what problem it's trying to solve, and install them on your computer if you want to follow along:

- POSIX tools and Bash scripting:

curl,cat, piping, looping, etc. (these should already be available on your computer if you're using OSX or Linux) - jq - parsing and processing of JSON

- yq - parsing and processing of YAML (it also

includes a tool

xqfor processing XML) - pup - parsing and processing of HTML

- csvkit - a collection of tools for reading, processing, and writing CSV files

NOTE: in the bash script examples below, I've broken commands across

multiple lines to make them easier to read (look for the trailing \ character

to escape the line break). If you have everything installed, you should be able

to copy and paste them into your terminal and try them yourself. Your terminal

emulator or shell may not like the comments (the lines leading with #) so try

removing them if your shell complains.

NOTE: these comands assume a Linux or POSIX-style computing system. Windows users may want to look into the Windows Subsystem for Linux to follow along. Just be warned I don't have a Windows machine to test, so please leave me a comment if something doesn't work for you and we'll try to get it figured out.

Finding Store URLs

Odds are you are interested in auditing a domain for which you don't already have the store locations. In that case, you need to determine if the store landing pages are already indexed somewhere on the domain. We'll look at a few common approaches:

- extracting a domain's sitemap

- scraping a store locator search portal

- extracting from some other feed

Let's look at each approach.

Locations Sitemap

Large sites should have a robots.txt and a sitemap.xml, or some equivalent.

Essentially, it's a way for a site to indicate to programs—crawlers, spiders,

what we're about to do, etc.—what pages exist in a domain and are interesting to

consume.

Some sites with an emphasis in local commerce may host their stores in the sitemap, or in a specific sub-sitemap dedicated to stores.

I have three ways I like to find these:

- Navigate to

/robots.txton the domain to see what sitemaps are listed - Use Google to search a domain for a page named or containing "sitemap" with

the following query:

site:somedomain.com sitemap - Use Google to search a domain for a page ending in an XML or JSON format:

site:somedomain.com filetype:xml

Let's look at anthropologie.com as an example.

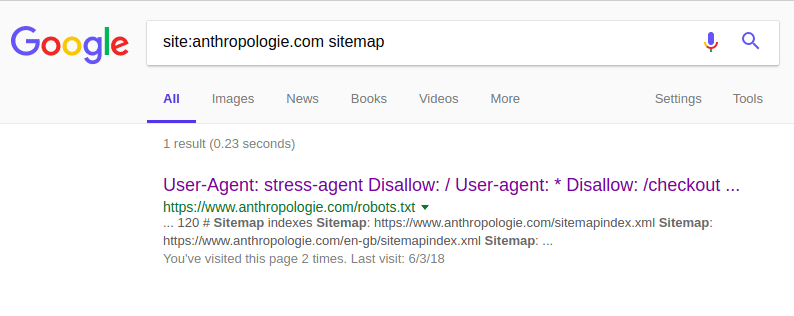

When we try the first Google search approach, we get a link to its robots.txt

file instead:

These files typically list sitemaps for crawlers to consume, so we click into

that and find a few entries by language and market. Clicking into the main

sitemapindex.xml, we find that it lists sub-sitemaps for various ways it

organizes the information in its domain: products, categories, wedding

registries, and so on.

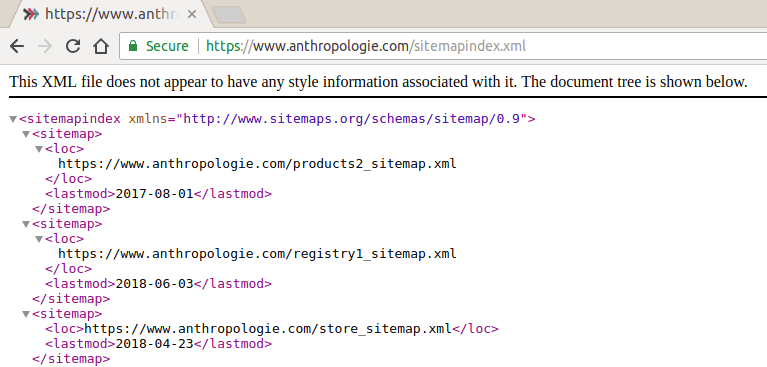

Most interesting to us is a store_sitemap.xml:

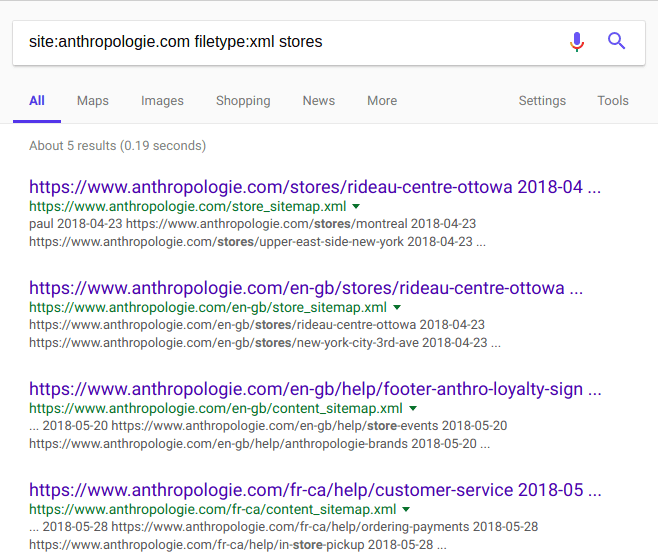

We could have arrived here another way. Let's look at searching by filetype. Use

Google's filetype: search operator to limit results to files hosted on the

domain matching the given file extension.

Sitemaps typically codify their site indexes in XML as it is a long-standing machine-readable format. However, JSON is also a popular format for encoding this kind of content. We can use Google's index to see what data is available in various formats so we don't miss any of the information out there.

Using filetype:xml, we can see all the XML files hosted on anthropologie.com

that Google knows about. This example shows that we can also add additional

search parameters to explore with some finesse:

Great, so we found all the stores Anthropologie has on its domain at its

store_sitemap.xml file. If

you've ever seen a sitemap XML file before, they follow a standard format and so

does this file. There is a root urlset node with url entries (usually called

"child nodes" or "children"). Each url node has a loc node that contains the

URL we want for the landing page for each store.

Ok, we need a quick way to pull those out. We're going to use some of our aforementioned CLI tools:

# We download the contents of the sitemap using curl. Notice how we use '-s'

# to suppress the usual progress output

curl -s https://www.anthropologie.com/store_sitemap.xml \

# We use the 'pipe' operator to read the output of curl as the input of

# 'xq'. We give it a path similar to CSS selectors to describe what we want

# to extract from the XML. Note the use of '-r' to get the raw response,

# stripped of quotes

| xq -r '.urlset.url[].loc' \

# Finally, we write everything to a file. The '>' operator is a redirect

# operator that sends the output of the previous command to somewhere

# else--in this case, a file

> anthropologie-urls.txt

Not every site will be organized the same way. Some sites keep their stores in the main sitemap. Others may maintain different sitemaps for each market or language.

You can still use these tools to explore, adapt to the variations, and get the contents of machine-readable contents into a file you can work with.

Store Locator Pages

Not every site organizes their stores like Anthropologie does. Let's look at Mercedes-Benz USA.

When we use all the approaches we learned in the previous section we don't find

the same kind of indexed XML sitemap we found on the other site. Even when

peeking at its robots.txt to find the URL

of its sitemap.xml file, scanning through that with xq doesn't reveal a list

of URLs for its dealership locations.

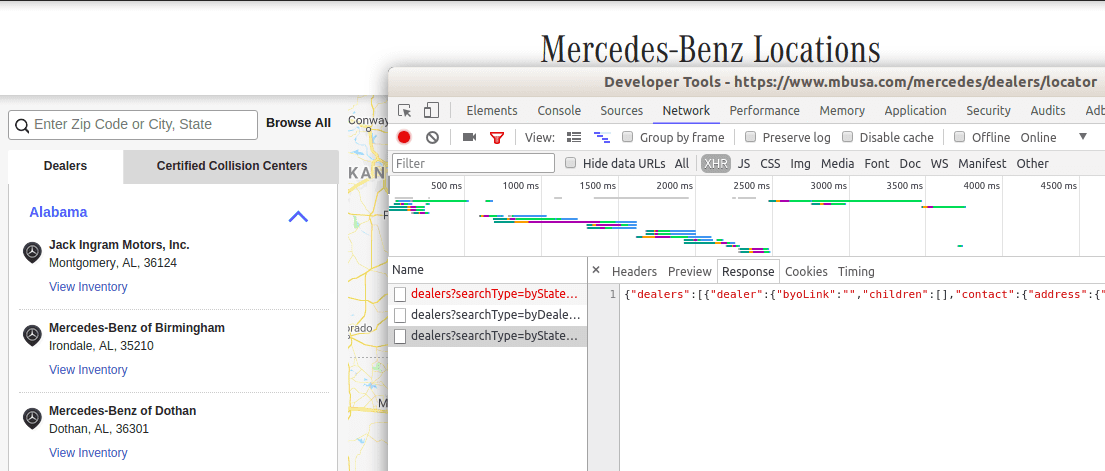

Instead, we find a URL for its dealership locator that looks promising. Opening that up, we're presented with a search UI. This is a human-friendly approach to access the inventory of landing pages, but we need something more amenable to extraction.

The high-level idea is to learn how the search UI talks to the backend to fetch search results, and mimic those requests with our tools.

Open the developer tools in your browser and use the Network inspector to watch what requests the search UI makes as you use it:

We see that each click on a state makes a request with the USPS state abbreviation encoded into the query parameters. The search results are encoded in JSON with each response. We can work with that.

Here is our plan:

- Get a list of all USPS state abbreviations and save it to a file

- Format the state into the dealership results URL

- Parse each JSON response to extract the dealership locations URLs

- Append all those URLs to a final results file

# We use 'cat' to output the contents of our state abbreviations file to the

# stream

cat states.txt \

# 'xargs' lets us run the same command for each row in the input. We use

# '-I{}' as a replacement placeholder in the sub-command to build a URL for

# each state in our list

| xargs -I{} curl -s "https://www.mbusa.com/mercedes/json/dealers?searchType=byState&state={}&trim=true" \

# We pipe the JSON response of each command to 'jq' similar to how we used

# 'xq' before. This is the path to get the store URL from each 'dealer' object

# in the 'dealers' array.

| jq -r '.dealers[].dealer.contact.url' \

# We redirect to a file again, but we use '>>' to append rather than overwrite

# the contents on each run

>> mbusa-urls.txt

Other Encoding Format Feeds

The vast majority of store indexes that I've seen so far have been in sitemaps or scraped from store locators. Every once in a while something comes along that makes it easier.

Check out what Arby's did. Not only do they have a locations.arbys.com domain to organize their stores, they have a datafeed published in JSON-LD format for all its stores.

JSON-LD is a subject for another post, but it is one way to encode a vocabulary defined at schema.org. This vocabulary is useful for encoding lots of information on the Internet, but it is also great for marking up business locations.

From the Arby's feed, we can pull out each store's landing page URL. Moreover, the rest of the store NAP data we want are right in the feed so we would be done.

I haven't seen this too often, but that doesn't mean there aren't more like that. Make sure you spend a lot of time exploring domains and sub-domains to find all your options before diving in. You might be able to save yourself a lot of time

Extracting NAP from Landing Pages

Once you obtain a list of URLs for the store landing pages in a domain, you need to find a way to extract the NAP data contained in the HTML and export it for further analysis.

This problem can be easier to solve when page authors employ structured data or semantic tagging to mark up NAP information.

Here too, you need to do a little surveying to decide which approach to use.

Pick one of the pages at random from the list you found and open it in a browser. First, I use my eyes to find where the NAP data is within the page structure. Once I have that, I spot check among a few more pages to see if the layout is consistent across the domain. This is likely if the site owner uses a CMS or some other means to generate store pages.

Once I know I have a standardized layout, I use the developer tools in my browser to see how that NAP is marked up. I can use that markup for programmatic extraction, and we'll explore a few possibilities next.

Structured Data with JSON-LD

JSON-LD is a machine-readable format for describing data and related objects built into the existing JSON format (which is itself just a subset of JavaScript).

It is useful for adding additional structured content to a page using the schema.org vocabulary. Schema.org is a community-powered and open-source effort offering a standardized way to describe objects on the Web and the relationships among them.

Useful for our purposes are schemas defined for "LocalBusiness" and "Store". We have a strong guarantee of finding published NAP data in an extractable format if we find those in the page.

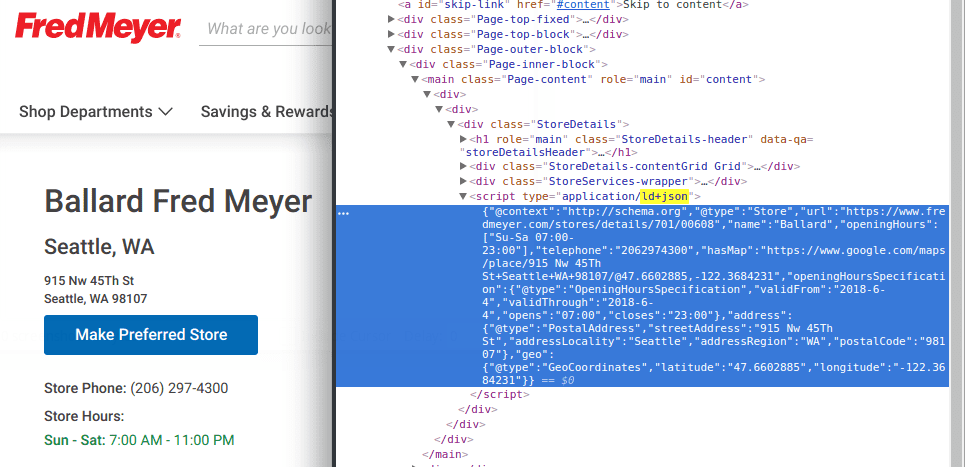

I like to start by using the browser's developer tools to search within the page HTML for the telltale signature of JSON-LD in a page

<script type="application/ld+json">

We mentioned Fred Meyer earlier when looking at landing pages. Their site content team uses JSON-LD to encode the store NAP data in the page:

They use the Store schema to mark up the store, and the schema includes an

address property. If that holds true for all Fred Meyer store landing pages, we

can use the following approach to extract all the NAP data:

- Download the HTML for all pages

- Use

pupto find JSON-LD nodes and extract their contents - Pipe each into

jq, filter toStoreentries, and extract the address contents

That looks something like this:

# This script is a bit more complicated only because it combines more steps. So

# we organize our steps into little functions and use bash script control

# operators to loop through results.

# find_urls gets all store URLs from the sitemap. Fred Meyer won't reply to # us

if it thinks we are a script, so we sent a user agent.

find_urls () {

curl -s 'https://www.fredmeyer.com/storelocator-sitemap.xml' \

-H 'user-agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Ubuntu Chromium/66.0.3359.181 Chrome/66.0.3359.181 Safari/537.36' \

| xq -r '.urlset.url[].loc'

}

# extract_from_url takes the URL for each store landing page (contained in the

# $1 argument variable) and processes it

extract_from_url () {

curl -s -H 'user-agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Ubuntu Chromium/66.0.3359.181 Chrome/66.0.3359.181 Safari/537.36' $1 \

# pup allows us to extract all nodes containing JSON-LD and output its

# contents

| pup 'script[type="application/ld+json"] text{}' \

# We get their contents as HTML-escaped text, so we convert the quotes back

| sed 's/"/"/g' \

# Then we run through jq to pick out the fields and objects we like.

# The '-c' flag tells jq to flatten the result to 1 line

# The JSON-LD content includes a '@type' field we don't need, so we can build

# data pipelines *within* jq programs. Here we send the result to the 'del'

# operator to remove that field.

| jq -c '({ name, url, telephone } + .address) | del(.["@type"])'

}

# Now we put it all together by looping through each result of calling

# find_urls, assigning it to the loop variable 'url', and then applying

# it to the extraction function.

for url in $(find_urls); do

extract_from_url $url

done

Structured Data with Microdata

Microdata is a mini-language built into HTML to add additional structured markup inline with your content. Similar to JSON-LD, you can use it to make your content more machine-readable, and it can be paired with the schema.org vocabulary to describe your content.

In this case, the best thing to look for is itemscope and itemprop. The

former indicates a beginning of the new object being described in the HTML

hierarchy, and the latter indicates what kind of object it is as defined by

the schema.

We'll speed things up here. In this example, we've found a page for a J. Crew outlet North of Seattle.

This script allows us to extract the NAP data from the Place object in its HTML:

curl -s https://stores.factory.jcrew.com/en/j-crew-factory-seattle-premium-outlets \

# Here I've broken up the 'pup' path into multiple lines to make it easier to

# read. Just like CSS, I can specify HTML nodes to extract with respect to

# their parent nodes. In this case, I want to start with the Place node...

| pup '[itemtype="http://schema.org/Place"]' \

# Then drill down to both the PostalAddress node and the peer phone node

# using the comma operator in the path...

' [itemtype="http://schema.org/PostalAddress"] meta, meta[itemprop="telephone"]' \

# Then I want to spit out what I find in JSON format

' json{}' \

# This jq program may look hairy, but I'm building up a final object from the

# list of HTML nodes I found, using the itemprop as the key and the content as

# the value.

| jq -c 'reduce .[] as $property ({}; .[$property.itemprop] |= $property.content)'

Semantic Markup and CSS Path Selection

If a page uses neither JSON-LD nor Microdata to mark up the NAP components, you

can still use pup to extract the data using other HTML selectors. If you

consider that Microdata and JSON-LD nodes are just HTML elements, then you

may be able to use the vanilla HTML to describe the path to the content you

want.

Here are some examples to consider:

- Target telephone

links with

pup 'a[href^="tel:"]' - Target address

tags with

pup 'address' - Target the existing HTML structure. For example, a site may include its

contact address in the footer:

pup 'footer .address li'

Again, each site will be different, but if you are willing to peek at the HTML structure and describe a path to an HTML node, you can still extract the data you want.

Exporting to CSV

Once you have all the landing pages identified and the NAP data extracted, you need to find a more convenient way to share the findings. Sending shell scripts and JSON content probably won't work outside of the tech department.

CSV is a simple format that is easy to create, share, and consume, and command-line tools exist to sit in a data pipeline and create CSVs for you.

csvkit is a family of tools you can use to consume, transform, and create CSV files. It can also parse input data in a variety of formats, including JSON.

Let's build on a previous example and use

in2csv to turn

our data pipeline into a file we can share.

Remember the Fred Meyer example? Let's assume we wrote all the NAP data to a file, with each line containing the NAP data we extracted for a site in JSON format.

We'll pipe that into in2csv to transform the JSON to CSV format:

# `.ndjson` is "newline delimited JSON"

cat fred-meyer-nap.ndjson | in2csv -f ndjson > fred-meyer-nap.csv

Next Steps

From here, you have some data to analyze. You can compare this information to what a company thinks their store information is to look for inconsistencies and correct them. This could be a starting point to add data about stores and upload the file to a listing management service or a directory.

And of course, if you don't have this, this is a good conversation to have with clients and stakeholders about the value of having a site and data strategy that is easy for humans to consume and search engines to crawl.

If you found a domain and some commands that worked, you can also save all the commands to a file and run them later. This is helpful if you want to compare results over time.

To do that, open a new file, give it a name, and save it somewhere you'll

remember it later. I like to use the .sh extension for shell scripts, but it

really doesn't matter.

Give your shell script a header so that the shell knows what interpreter to use for the contents. These are sometimes called "shebangs" or "hashbangs" and it helps me remember the order of characters to enter:

#! env bash

NOTE: you'll sometimes see /bin/bash, /usr/bin/bash, or /bin/sh

depending on your operating system. I like to use env since that just looks up

where the bash program is on your computer.

Save all the commands you ran below the header in that file and save it.

Then you run the chmod command on your computer to make it executable:

chmod +x somescript.sh

From there, you can run it later like this: ./somescript.sh

NOTE: somebody already familiar with POSIX systems may be wondering why I

didn't introduce the notion of a ~/bin folder and adding it to $PATH. I'm

just trying to keep it simple for now, and that's a lesson for another day.

A Programmer's Take

This post is really about 2 things in my mind:

- Leveraging SEO concepts to audit a business domain

- Composing simple, existing technical tools to create cheap and flexible solutions

As much as I find the business domain interesting, I'm also advocating for simple technical ideas found in the UNIX philosophy:

- Small is beautiful.

- Make each program do one thing well.

- Build a prototype as soon as possible.

- Choose portability over efficiency.

- Store data in flat text files.

- Use software leverage to your advantage.

- Use shell scripts to increase leverage and portability.

- Avoid captive user interfaces.

- Make every program a filter.

Each site you audit is going to be unique. The requirements are likely to change. Trying to write code from scratch for every audit is going to be expensive, exhausting, and ultimately a waste of time.

You don't need to re-implement HTTP fetching, site parsing, or CSV writing every time.

Instead, you should leverage existing tools that solve known problems, and save your brain space for the interesting parts of your problem.

This post is also meant to expose you to these small powerful tools to compose them into a powerful solution for each new problem.

Wrapping Up

Ok, that was a long one! I may not have anticipated every person that may come across this information, nor considered all the problems you may encounter. My hope is you might be able to use some or all of these ideas to make your life easier.

So here's what I hope people leave with:

- These cool little CLI tools exist! Even if you don't use them for NAP extraction, I have found applications for them in so many problems.

- Marketers at organizations without engineering support: rather than wading through a tutorial for a massive library that doesn't exactly fit your problem, I hope you have a few new tools you can tweak to help you out

- Marketers at organizations with engineering teams: this isn't meant to be freedom from your engineering teams; think of this as tools and ideas to work more effectively with your teams to arrive at solutions sooner

- Engineers: I hope you learned a few cool tools and shell tricks, but I also hope you saw some value in composing small tools into cooler solutions. Also, you should learn a little bit about SEO, marketing, and site management. It's not a huge leap from what you already know and it makes you a more well-rounded team member

Please let me know if I left something out or something is unclear. I'll be happy to work with you to get it resolved and update the post.

Thanks for reading!